What Motivates American Workers in the “Great Resignation”

Remote Working Is Here to Stay

Among the unexpected consequences of the pandemic is the so-called “Great Resignation.” There are two separate phases of this phenomenon. In the first phase, many manual laborers used the forced vacation paid for by the government as a launch pad to new careers. In the second phase, tech workers decided they did not want to return to the office because they fell in love with remote working. As businesses asked them to come back, they quit looking for remote-only jobs.

I’m hearing from business owners that remotely motivating employees is hard, which is probably the reason many of them are calling them back into the office. But, now, some of these remote workers are literally doubling down, secretly holding two full-time remote jobs. overemployed.com is a website that tells you how to pull it off.

There are certainly communication challenges with remote working. The most common complaint is that technologies like Zoom are lacking in their ability to share emotions accurately, particularly when multiple people are involved. There is something about being physically present with other people that excites us, which is why many people still pay a lot of money to see bands play in person despite the advancement in audio-visual technologies. But this type of collective euphoria should not be confused with motivation. Just because a group of motivated people looks excited about being together, it doesn’t mean that being together is what is motivating them. Motivation, like a shared goal, exists separately and is enhanced by being in the presence of each other.

Some companies mistake the effect for the cause. Rituals like team-building exercises, company trips, chanting, singing, and dancing are used to motivate employees. It may work to some degree, particularly for people with a herd mentality, but in the long run, no amount of rituals will get employees excited about selling snake oil.

After all, how often do you walk away feeling excited from company meetings, even if they take place in person? Many people find them boring and unproductive because the loudest people tend to monopolize everyone’s time with their self-aggrandizing monologues. That is, in-person meetings often have the opposite problem; they are dominated by emotional content and are ineffective in communicating the substance.

However, the pros and cons of the different modes of communication are not relevant here because remote working won’t be going away. Whether you like it or not, you have to have strategies to maximize its strengths and minimize its weaknesses. Being independent of location means more opportunities for employees and more candidates for employers. Employees save time by not having to commute. Employers save money on real estate and IT infrastructure. We have to look at it as a glass half full.

So, I would say fighting this wave is futile. Employers must think about how to motivate employees remotely.

The Ethics of Having Two Jobs

Before diving into solutions, let’s think about the ethics of having two jobs. For many people, what is attractive about remote work is that they can do something else while working, even if it’s not a second job. I’ve read that many parents with small children love it because they get to spend more time with them. Either way, there is a question of ethics here.

If you are a full-time employee, you are getting paid for your time. Typically, this means you dedicate 9 am to 5 pm to your employer. In exchange, your employer protects you from financial uncertainties. As long as you put in those hours, they pay you even if the business loses money.

If you run an agency business, you are keenly aware of this because for some projects, you give your clients a fixed fee per project, while for others, you bill them hourly. Clients obviously prefer knowing exactly how much something will cost in advance, but this involves risks for agencies because things do not always go according to plan. For example, sometimes, you might end up spending 100 hours on a project that you estimated to take only 50 hours. Other times, you might finish a similar project in 25 hours. So, a fixed price must always include a risk management fee or a risk premium.

In contrast, when you bill hourly, your client must manage the risk. You would get paid no matter how long it takes. In fact, the longer it drags on, the more money you make.

“Overemployed” workers argue that how they spend time should not matter to employers as long as they are delivering what the employers need. This argument would be justifiable if they were giving the employers a fixed price for a specific deliverable and taking on the financial risks, but, as full-time employees, that is not the case. If they finish an assigned task in 5 hours when 10 hours is the norm, they pocket the difference (work for the other employer or spend time with their kids), but what happens if they end up taking 15 hours? Do they pay back the lost 5 hours? No. The employer still has to pay for them.

So, they are trying to cherrypick the sweet parts of fixed pricing and hourly billing and get away with it. This is not ethical. If they want to act like a business owner and charge for deliverables, then they need to accept the risks associated with it. They should not live a fantasy of being a business owner at the expense of another business owner.

Pros and Cons of Monitoring Employees

But just because you are right and they are wrong doesn’t mean stating that fact would motivate them to work harder. In fact, the opposite would be true. As one of my business owner friends said: Would you rather be right or happy? Because you can’t be both!

One obvious solution is to monitor your employees with tools like Hubstaff and ActivTrak. If their mice are not moving for hours or if they are spending hours on Netflix, it’s likely that they are not working. As tempting as this solution is, there are some negative consequences.

The mere act of observing can change people’s behavior. In fact, you don’t even need to observe as long as they think they are being observed. Panopticon is an architectural design that takes advantage of this. One security guard can monitor the entire prison because prisoners are unable to see the guard. Even though it’s impossible for a single guard to monitor all prisoners at all times, it works to moderate the prisoners’ behavior. Most of us act awkwardly when a video camera is pointed at us, even if we are told to relax. This self-consciousness or internalized gaze can be draining and counter-productive. Although the monitoring tools mentioned above do not have video cameras pointing at employees, they continually monitor their activities on their computers which has the similar effect of being watched by a security guard. For instance, I personally write differently when I’m on Google Docs and someone else is watching as I type.

Here, we should differentiate between monitoring and measuring because they do not entirely overlap. From the employees’ point of view, there is no positive side to monitoring (that I can think of), although the benefits to employers are obvious. For freelancers who bill hourly, like on Upwork, monitoring is beneficial for preventing disputes, but full-time employees have no such needs. The one-sided nature of the arrangement will likely damage employee morale.

However, many employees confident of their abilities want to be measured if their compensations are dependent on it. It usually involves only one metric, like the number of orders processed or a monthly sales figure, so it doesn’t feel like Big Brother is watching all the time.

But there are negative consequences of measuring too. Measuring anything encourages one-dimensional thinking, which is less creative and relevant. The SAT is a good example. The skills, knowledge, and self-discipline required to score high on it may be useful in some aspects of our lives, but it is certainly not predictive of many different ways we can succeed. The same is true for what constitutes “success” for your business. If you, as their employer, told your employees that X is the data you will use to calculate their compensation or evaluation for pay raises or promotions, they are not going to question whether X is indeed the right data to focus on. They are going to only care about X and nothing else. After all, what would be in it for them to question it?

On Wall Street, for instance, many traders abuse the trust and reputation of their employers for short-term gains as their bonuses are directly proportionate to profits. Since they do not expect to work for the same firms for long, they don’t care what happens to the reputation of their employers. The financial crisis of 2008 was a result of abusing the trust of the American people for short-term gains.

We have to be careful of what we measure, as it can incentivize people to act selfishly. When you tell people to be responsible for only one thing, you are, in essence, telling them that you would be responsible for everything else.

The most significant problem I see with measuring is that creativity cannot be measured. You can measure the time it took to arrive at a creative solution, but it would have no relation to the level of creativity. Furthermore, being self-conscious of time will likely have a negative impact on the creative outcome. In general, the tasks whose productivity can be measured do not require creativity. They are the types that will eventually be eliminated through automation. The tasks that have the greatest impact on your business are the ones that require creativity, and measuring them will likely lead to negative consequences because creativity is inherently multi-dimensional, and it’s not possible to measure all of them.

Take a simple example of logo design. The time a designer spends on it does not correlate with the quality. One designer could come up with an amazing idea in five minutes, while another designer might struggle for ten hours without a satisfactory result. Even a talented designer cannot consistently produce an outstanding result on every project.

The same holds for engineers trying to solve novel problems. Given that nobody has solved the same problem before, there is no way to estimate how long an engineer should take to arrive at the solution. And, even if the solution sounds great, there is no guarantee that the product will sell.

Measuring productivity also risks starting off on the wrong foot in negotiating or debating with your employees. It implies that you are paying for productivity, not their time. This will only support their argument that they should be free to do whatever they want with saved time as long as their productivity is in line with your expectation. And, if you ask them to increase their productivity by making use of their saved time, they will naturally ask for more money as you are the one who is implying that pay should be proportionate to productivity. If you are willing to offer that, there is no problem, but are you really ready to go down that path?

Possible Solutions

If not productivity, what should employers be paying for? I would argue that you should pay for their allegiance to the shared purpose. Here is a hypothetical comparison: Employee A is highly competent and efficient but doesn’t care about the purpose, and Employee B takes twice as long to do the same tasks as A but is deeply passionate about the purpose. Which one would you choose?

If you only cared about short-term productivity, Employee A would be a better choice, but Employee B can potentially bring other benefits to your business in the long run. Creativity is priceless, so Employee A would have no incentive to contribute it to your business. Two of the “12 Rules” on overemployed.com are “try not to be recognized” and “don’t do extra.” Offering creative solutions is how you get recognized and end up with extra work. Remember: creative people are not necessarily efficient because creativity and efficiency are on different sides of our brains.

Increasing efficiency is easily achievable if there is a will for it. Any employee who cares about the shared purpose will naturally increase it over time. So, even if he is half as efficient as Employee A now, it’s only a matter of time before he catches up.

Allegiance is relatively easy to detect, even if it’s not measurable. In fact, we can use the “12 Rules” of overemployed.com as our guide to identifying it.

Rule #1 is “Don’t talk about working two remote jobs.” Do your employees list your company on their LinkedIn profiles? When they achieve something they feel proud of, do they share it on social media? Do you hear them talking to their friends about their jobs? When there is an open position, do they recommend their friends?

Rule #2 is “Don’t fall in love with your jobs.” When you are in love with someone, you cannot help but care about her well-being. You want her to be happier. You are not thinking about what’s in it for you. So, you volunteer whatever help you can offer. Suggesting ideas comes naturally in this process. If your employees offer unsolicited advice or ideas, it’s a pretty good sign that they care about the shared purpose.

Rule #6 is “Get what you want by giving people what they want,” and it provides an example: “Whether you are confident or not, you just need to feed them those cues and give them what they want to see/hear.” So, what is the opposite of this? Employees who criticize and disagree with you. Sometimes, loving someone requires unpleasant confrontations. If your employees do not criticize or disagree with you, it could mean they are indifferent.

Also, do your employees clarify what they want? Do they share their long-term goals and dreams? If you love someone, it’s only natural that you want her to love you back, and to be loved, you have to be vulnerable and reveal your desires. If you can align your purpose with their purpose, they will be on autopilot to your desired destination. You wouldn’t have to monitor them.

Rule #7 is “Be average,” and it goes on to explain that the more attention you bring to yourself, the more people will remember you. It’s true; passionate people are memorable. Are your employees memorable?

Rule #9 is “Have no ego; be wrong to be “rich.” Here is an example it provides: “Can you stomach just doing a mediocre job and being judged by your peers?” This is a misuse of the term “ego.” None of us would have a problem letting others judge us if we do not care about them. Just because you do not care what your coworkers think of you doesn’t mean you have no ego. Your ego might just be expressed elsewhere, like being “rich.” And, just because you do care about what others think doesn’t mean you are egotistical either. Ultimately what matters is whether your ego is in sync with what you are (ego-syntonic vs. ego-dystonic). If you want to be a mobster, your reality as a murderer is in sync with what your ego wants, so you’d be happy.

Because we humans are social creatures, we naturally enjoy engaging others, but to enjoy it, we must be true to ourselves. This is not related to your ego. Deliberately doing a “mediocre job” would deprive you of this enjoyment.

What American Workers Want

These rules teach people how to ignore other people’s purpose and worry only about their own. A room full of employees with their own separate purposes would not have any synergetic effect even if they are efficient. 1 + 1 would produce exactly 2. On the other hand, a room full of employees whose allegiance is to the same purpose would achieve a result many times greater than the sum of its parts. Your employee’s heart can compensate for a deficiency in his brain, but his brain will not compensate for a deficiency in his heart.

Those in the creative industry, like graphic designers, are familiar with this problem. When they begin worrying about efficiency, productivity, and the bottom line, the quality of work suffers because it strips the joy out of creating beautiful things. Successful designers I know spend their free time doing graphic design because they enjoy it. If they were to measure their productivity, their hourly rate would plummet, but they don’t care. But at the same time, they cannot completely ignore the bottom line either.

In The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho, there is a story that nicely illustrates this dilemma:

The Sage told a young man to walk around his palace holding a spoon full of oil. When he returned, the Sage asked if he saw all the beautiful artworks. The young man said he was too concerned about the oil that he didn’t notice anything. The Sage then told him to walk around again and pay attention to all the works of art. He came back impressed by the beautiful things he saw, but he had spilled the oil along the way. The Sage told him: “The Secret of Happiness lies in looking at all the wonders of the world and never forgetting the two drops of oil in the spoon.”

What the Great Resignation is telling us is that American workers are looking for meaning in life, and they are not finding it in their jobs, which is why some of them have given up looking for meaning in jobs. They don’t have to be reminded of the two drops of oil in the spoon, that is, the need to be productive. Their problem is that they don’t see any “wonders” in their work.

After World War II, Japan was a poor nation. When people are desperate, there is no need to motivate them because the survival instinct alone would suffice. But as Japan became wealthier, they began to question the point of working so hard. Japan is no longer hell-bent on being the most efficient and productive economy in the world. Now, China is in that phase, which is why Chinese parents are preoccupied with their children’s test scores. Americans are beyond Japan and China. American children won’t be able to compete with the kids in developing nations whose focus on efficiency is a matter of life and death. So, why even try? America must compete with creativity, and for that, the heart is more important than the brain, as the latter is a commodity that can easily be bought today. You might think if you treat your employees with respect and pay them well, throwing in pool tables and unlimited vacations, they will work hard, but Americans are looking for much more than that.

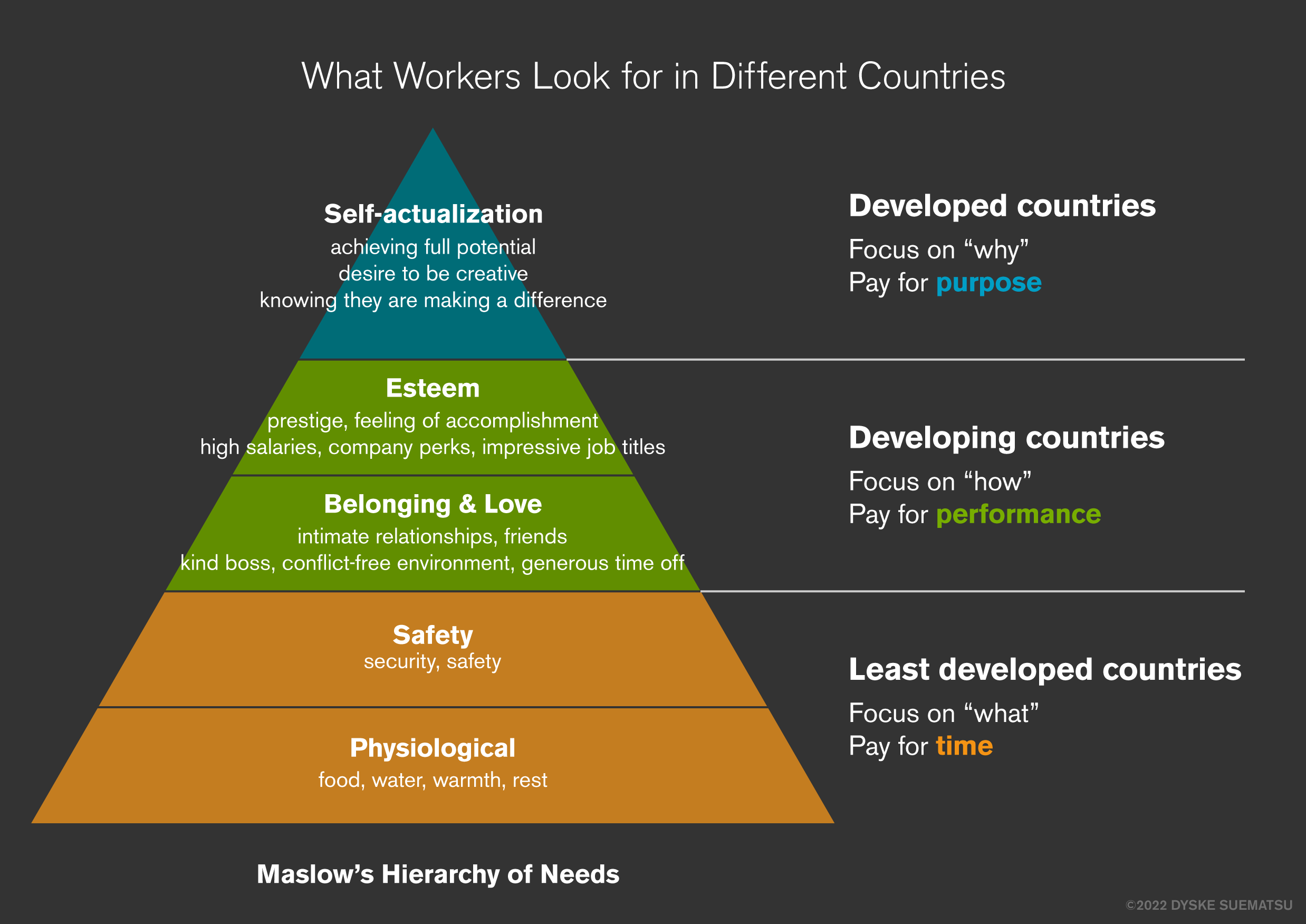

Why do cooks and chefs in the restaurant industry work so hard for so little? Shouting and swearing, which are deemed unprofessional in a corporate environment, are commonly tolerated in the restaurant industry. Why did Apple engineers tolerate Steve Jobs’ notoriously abusive management style? Because they were working for a cause greater than their boss. They believed in what they were doing. “Self-actualization” in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is what American workers want, to know that they are living purposefully and making a difference. American businesses need not people who can answer complex questions but those who can ask the right questions. And, American workers are indeed asking meaningful, existential questions. Businesses that also ask these questions should succeed because American workers are also the greatest consumers in the world.

By Dyske Suematsu (dyske@cycleia.com)

Photo by Kristin Wilson on Unsplash