Mystery Solved: Why Some People Love Twitter — and Why Others Don’t

If you Google “Twitter is stupid”, you will find many people asking what Twitter is good for and why some people love it so much. They have tried and found it utterly useless. I did too. Since Twitter was founded in 2006, I’ve tried at least three different times in the past, dedicating a significant amount of time learning about Twitter and using it, and every time, I failed to understand the point of it. Sure, we all have things we don’t enjoy that others passionately love. I have no interest in watching sports, but I can at least understand why many people love it. What bothers me about Twitter is that I do not understand it even theoretically. But now I think I’ve finally solved this big mystery.

First let’s consider the arguments against Twitter. Twitter cannot function effectively as a news aggregator (like RSS readers) because so much of the content is people making casual remarks. Important pieces of information get buried in the noise. Twitter cannot help us keep in touch with our friends and families because most of us do not actively use it. (Most of my own “followers” are strangers.) We cannot share meaningful ideas because of the number of characters allowed is capped at 140. It’s just enough to share the title and the URL of the article you want to share. It’s not a great place to share photos either; Instagram can do that much better.

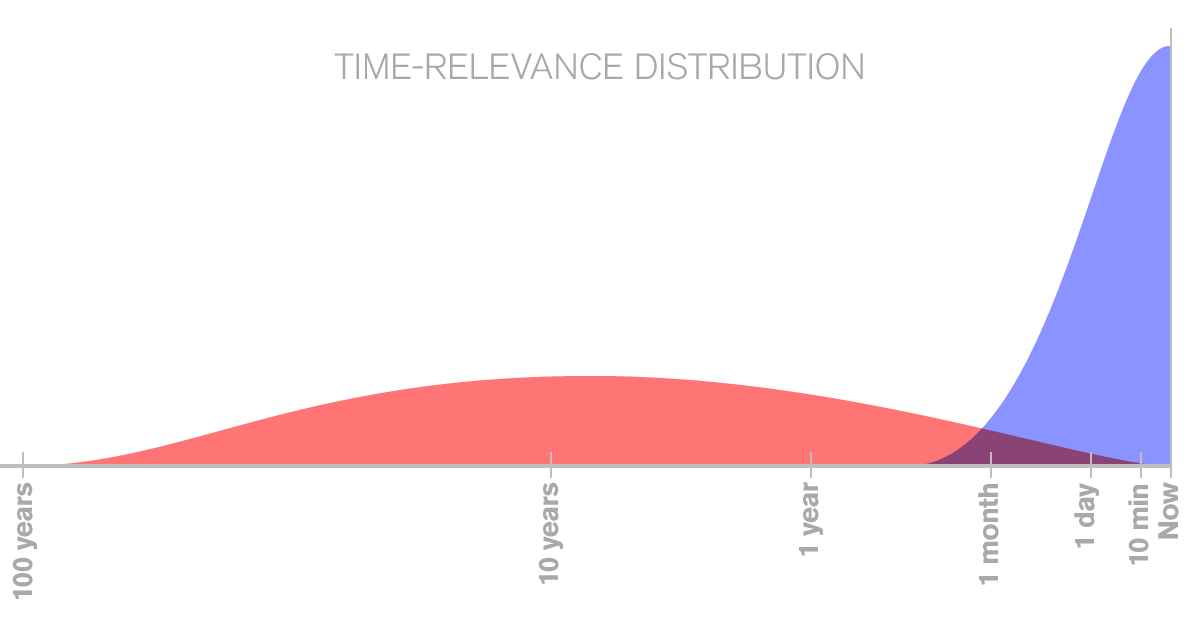

So, why do anyone use Twitter? There are a few factors involved, and I found some explanations on the Web but the key concept that we need to understand is how our sense of relevance is distributed across time. Let’s call it “time-relevance distribution”. Compare, for instance, a Wall Street trader and a carpenter. In order to do their jobs well, they need information. Suppose we throw a hundred random pieces of information at them, and they are to pick the ones they find useful or interesting. We then place them on a timeline by looking at the time associated with each. One may be about the latest iPhone that Apple announced 10 minutes ago. The other may be about the research conducted on the archival characteristics of different types of wood which was published 10 years ago. Let’s say, the Wall Street trader found the former useful, so we place the former on the timeline at 10 minutes. The carpenter found the latter relevant to his job, so we place it on his timeline at 10 years. If we are to repeat this for all 100 pieces of information, we would probably get two distinct curves on the timeline. See the hypothetical graph below.

As you can see, the distribution of the Wall Street trader, as represented by the blue area, is heavily skewed to the recent past. To him, if any piece of information is more than a day old, it’s not particularly relevant or useful. In comparison, the carpenter, as represented by the red area, is not particularly concerned about the timeliness of the information. In fact, he is more interested in matters pertaining to timelessness.

Journalists, fashion designers, event planners, and weather forecasters are very much like the Wall Street trader. And, English teachers, philosophers, farmers, and whiskey makers are more like the carpenter. And, I believe we all naturally gravitate towards timeliness or timelessness. This is the key difference between those who use Twitter and those who don’t.

Twitter in real life is equivalent to CB radio where truck drivers share information about what is going on now with other truck drivers who happen to be near one another (who are also interested in the same information). Most of them wouldn’t be interested in hearing a recording of their communication from an hour ago.

In contrast, Facebook is equivalent to Post-it notes we leave for other people to see. We do not expect the others to be paying attention to it in real-time. (If the others are here now, we would rather tell them verbally.) On Facebook, we leave the information for others to consume within a day or two. The common mistake that people (including myself) make on Twitter is that they leave messages thinking that people would read them later (as they do on Facebook), but this is not what Twitter is really for.

Blogs extend time-relevance further. A typical blog is equivalent to a bulletin board where fliers can remain push-pinned for weeks. Some blog posts remain relevant for years, and people do find and read them through search engines. Many of my old posts continue to receive as many visitors as my latest one, because they enter my site directly to individual posts, bypassing the home page. The impact that home page has on the popularity of individual contents is becoming less significant these days because Google is functioning as their home page.

Time-relevance distribution of young people tends to be skewed toward the present, like that of the Wall Street trader above, because their own life experience is skewed towards the present. If you are 20 years old, things that happened in the last 20 years would naturally be more interesting to you than those that happened 50 years ago. And as we grow older, we become more interested in what remains timeless because we witness them in our own lives. (Teenagers cannot personally experience timelessness.) People who live in the city tend to be skewed towards the present than those who live in the country because things change much more quickly in urban areas.

Because time-relevance distribution is different for everyone, we naturally choose mediums that are more appropriate for our own. If you are primarily concerned about timeless matters, you are going to have a hard time understanding why anyone would use Twitter because there is nothing interesting for you in the highly compressed area of the timeline for which Twitter is optimized.

Twitter in essence is a reincarnation of AOL chat rooms. In the early 90s, most people weren’t paying much attention to the Internet until AOL introduced the idea of chat rooms. The rooms were generally divided by topics of interest, and strangers who shared the same interest came in and chatted with one another. Eventually they would form loose communities. This idea of chat rooms gradually waned in popularity but Twitter picked up where AOL left off. On the facade, Twitter does not look like an instant messaging program, but it does the same thing. The concept of “room” is replaced by “hashtag”. Hashtags form temporary rooms where those who share the same interest gather and chat. This is why the 140-character limit is still prevailing on Twitter; if you think about Twitter as a platform for real-time conversation (like instant messaging or texting), why would you need more than 140 characters? In a face-to-face conversation, if you kept talking for more than 140 words (without letting the other person talk), you would be considered rude.

Most of us use instant messaging or texting even if we don’t use Twitter. The only significant difference between the two is that Twitter is designed to connect and chat with strangers. It’s a public instant messaging platform (like AOL chat was). Many married people use instant messaging and texting with their own spouses to coordinate domestic duties. In the same way, Twitter users are sharing and coordinating information about events that are happening now, but with strangers. This is why it is highly useful for states of emergency like the Boston bombing and Hurricane Sandy. It is also useful for businesses like airlines, event venues, and Internet service providers who need to communicate with their customers in real-time on a public platform (so that they would not need to repeat the same information to every customer). To find Twitter useful, you must be interested not only in timely matters, but also in connecting with strangers.

My conclusion: If you do not have any need to coordinate and share information on a real-time basis with the general public, Twitter is not for you. For my own business, I need to be informed of the latest technologies but whether the information is an hour old or a month old makes no material difference. In other topics, I’m more interested in timeless matters. I would imagine that Twitter is useless for the majority of people. It is a tool for those whose time-relevance distribution is heavily compressed into matters of minutes and hours, not days or months. Very few people have such needs, but it does not necessarily mean that they are doing something “stupid” or superficial. The common hostility towards Twitter users comes from the fear of not knowing/understanding what they do. I too had this nagging feeling that I’m missing out on something important to everyone, which is what lead me to investigate. Now I think I can leave them alone in peace.